3.1. Settings¶

The Settings class provides a general purpose data container for various kinds of information that need to be stored and processed by PLAMS environment.

Other PLAMS objects (like for example Job, JobManager or GridRunner) have their own Settings instances that store data defining and adjusting their behavior.

The global scope Settings instance (config) is used for global settings.

It should be stressed here that there are no different types of Settings in the sense that there are no special subclasses of Settings for job settings, global settings etc.

Everything is stored in the same type of object and the role of a particular Settings instance is determined only by its content.

3.1.1. Tree-like structure¶

The Settings class is based on the regular Python dictionary (built-in class dict, tutorial can be found here) and in many aspects works just like it:

>>> s = Settings()

>>> s['abc'] = 283

>>> s[147147] = 'some string'

>>> print(s['abc'])

283

>>> del s[147147]

The main difference is that data in Settings can be stored in multilevel fashion, whereas an ordinary dictionary is just a flat structure of key-value pairs.

That means a sequence of keys can be used to store a value.

In the example below s['a'] is itself a Settings instance with two key-value pairs inside:

>>> s = Settings()

>>> s['a']['b'] = 'AB'

>>> s['a']['c'] = 'AC'

>>> s['x']['y'] = 10

>>> s['x']['z'] = 13

>>> s['x']['foo'][123] = 'even deeper'

>>> s['x']['foo']['bar'] = 183

>>> print(s)

a:

b: AB

c: AC

x:

foo:

123: even deeper

bar: 183

y: 10

z: 13

>>> print(s['x'])

foo:

123: even deeper

bar: 183

y: 10

z: 13

So for each key the value can be either a “proper value” (string, number, list etc.) or another Settings instance that creates a new level in the data hierarchy.

That way similar information can be arranged in subgroups that can be copied, moved and updated together.

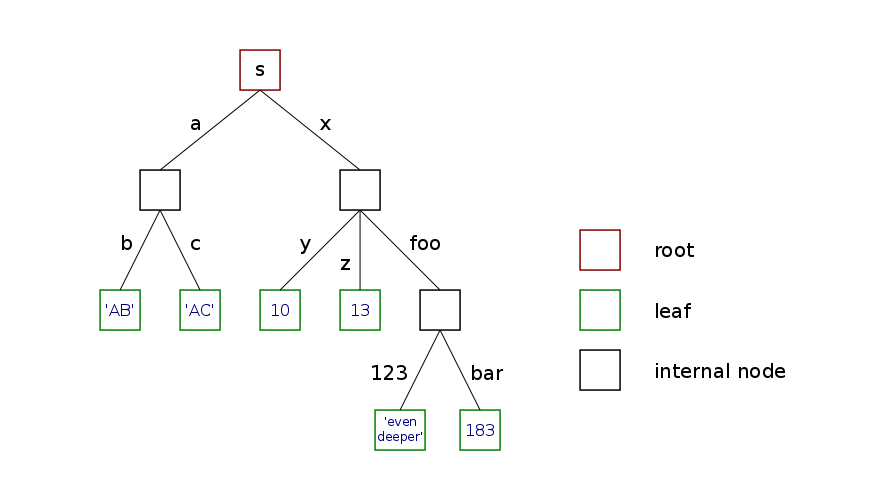

It is convenient to think of a Settings object as a tree.

The root of the tree is the top instance (s in the above example), “proper values” are stored in leaves (a leaf is a childless node) and internal nodes correspond to nested Settings instances (we will call them branches).

Tree representation of s from the example above is illustrated on the following picture:

Tree-like structure could also be achieved with regular dictionaries, but in a rather cumbersome way:

>>> d = dict()

>>> d['a'] = dict()

>>> d['a']['b'] = dict()

>>> d['a']['b']['c'] = dict()

>>> d['a']['b']['c']['d'] = 'ABCD'

===========================

>>> s = Settings()

>>> s['a']['b']['c']['d'] = 'ABCD'

In the last line of the above example all intermediate Settings instances are created and inserted automatically.

Such a behavior, however, has some downsides – every time you request a key that is not present in a particular Settings instance (for example as a result of a typo), a new empty instance is created and inserted as a value of this key.

This is different from dictionaries where exception is raised in such a case:

>>> d = dict()

>>> d['foo'] = 'bar'

>>> x = d['fo']

KeyError: 'fo'

===========================

>>> s = Settings()

>>> s['foo'] = 'bar'

>>> x = s['fo']

>>> print(s)

fo: #the value here is an empty Settings instance

foo: bar

3.1.2. Dot notation¶

To avoid inconvenient punctuation, keys stored in Settings can be accessed using the dot notation in addition to the usual bracket notation.

In other words s.abc works as a shortcut for s['abc'].

Both notations can be used interchangeably:

>>> s.a.b = 'AB'

>>> s['a'].c = 'AC'

>>> s.x['y'] = 10

>>> s['x']['z'] = 13

>>> s['x'].foo[123] = 'even deeper'

>>> s.x.foo.bar = 183

>>> print(s)

a:

b: AB

c: AC

x:

foo:

123: even deeper

bar: 183

y: 10

z: 13

Due to the internal limitation of the Python syntax parser, keys other than single word strings cannot work with that shortcut, for example:

>>> s.123.b.c = 12

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> s.q we.r.t.y = 'aaa'

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> s.5fr = True

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

In those cases one has to use the regular bracket notation:

>>> s[123].b.c = 12

>>> s['q we'].r.t.y = 'aaa'

>>> s['5fr'] = True

The dot shortcut does not work for keys which begin and end with two (or more) underscores (like __key__).

This is done on purpose to ensure that Python magic methods work properly.

3.1.3. Global settings¶

Global settings are stored in a public Settings instance named config.

They contain variables adjusting general behavior of PLAMS as well as default settings for various objects (jobs, job manager etc.)

The config instance is created during initialization of PLAMS environment (see init()) and populated by executing plams_defaults file.

It is visible in the main PLAMS namespace so every time you wish to adjust some settings you can simply type in your script, for example:

config.job.pickle = False

config.sleepstep = 10

These changes are going to affect only the script they are called from.

If you wish to permanently change some setting for all PLAMS executions, you can do it by editing plams_defaults, which is located in the root folder of the package ($ADFHOME/scripting/scm/plams).

Note

You can create multiple “profiles” of PLAMS behavior by creating multiple different copies of plams_defaults (also with different filenames).

If the environmental variable $PLAMSDEFAULTS is present and its value points to an existing file, this file is used instead of plams_defaults from the root folder.

3.1.4. API¶

-

class

Settings(*args, **kwargs)[source]¶ Automatic multi-level dictionary. Subclass of built-in class

dict.The shortcut dot notation (

s.basisinstead ofs['basis']) can be used for keys that:- are strings

- don’t contain whitespaces

- begin with a letter or an underscore

- don’t both begin and end with two or more underscores.

Iteration follows lexicographical order (via

sorted()function)Methods for displaying content (

__str__()and__repr__()) are overridden to recursively show nested instances in easy-readable format.Regular dictionaries (also multi-level ones) used as values (or passed to the constructor) are automatically transformed to

Settingsinstances:>>> s = Settings({'a': {1: 'a1', 2: 'a2'}, 'b': {1: 'b1', 2: 'b2'}}) >>> s.a[3] = {'x': {12: 'q', 34: 'w'}, 'y': 7} >>> print(s) a: 1: a1 2: a2 3: x: 12: q 34: w y: 7 b: 1: b1 2: b2

-

copy()[source]¶ Return a new instance that is a copy of this one. Nested

Settingsinstances are copied recursively, not linked.In practice this method works as a shallow copy: all “proper values” (leaf nodes) in the returned copy point to the same objects as the original instance (unless they are immutable, like

intortuple). However, nestedSettingsinstances (internal nodes) are copied in a deep-copy fashion. In other words, copying aSettingsinstance creates a brand new “tree skeleton” and populates its leaf nodes with values taken directly from the original instance.This behavior is illustrated by the following example:

>>> s = Settings() >>> s.a = 'string' >>> s.b = ['l','i','s','t'] >>> s.x.y = 12 >>> s.x.z = {'s','e','t'} >>> c = s.copy() >>> s.a += 'word' >>> s.b += [3] >>> s.x.u = 'new' >>> s.x.y += 10 >>> s.x.z.add(1) >>> print(c) a: string b: ['l', 'i', 's', 't', 3] x: y: 12 z: set([1, 's', 'e', 't']) >>> print(s) a: stringword b: ['l', 'i', 's', 't', 3] x: u: new y: 22 z: set([1, 's', 'e', 't'])

This method is also used when

copy.copy()is called.

-

soft_update(other)[source]¶ Update this instance with data from other, but do not overwrite existing keys. Nested

Settingsinstances are soft-updated recursively.In the following example

sandoare previously preparedSettingsinstances:>>> print(s) a: AA b: BB x: y1: XY1 y2: XY2 >>> print(o) a: O_AA c: O_CC x: y1: O_XY1 y3: O_XY3 >>> s.soft_update(o) >>> print(s) a: AA #original value s.a not overwritten by o.a b: BB c: O_CC x: y1: XY1 #original value s.x.y1 not overwritten by o.x.y1 y2: XY2 y3: O_XY3

Other can also be a regular dictionary. Of course in that case only top level keys are updated.

Shortcut

A += Bcan be used instead ofA.soft_update(B).

-

update(other)[source]¶ Update this instance with data from other, overwriting existing keys. Nested

Settingsinstances are updated recursively.In the following example

sandoare previously preparedSettingsinstances:>>> print(s) a: AA b: BB x: y1: XY1 y2: XY2 >>> print(o) a: O_AA c: O_CC x: y1: O_XY1 y3: O_XY3 >>> s.update(o) >>> print(s) a: O_AA #original value s.a overwritten by o.a b: BB c: O_CC x: y1: O_XY1 #original value s.x.y1 overwritten by o.x.y1 y2: XY2 y3: O_XY3

Other can also be a regular dictionary. Of course in that case only top level keys are updated.

-

merge(other)[source]¶ Return new instance of

Settingsthat is a copy of this instance soft-updated with other.Shortcut

A + Bcan be used instead ofA.merge(B).

-

find_case(key)[source]¶ Check if this instance contains a key consisting of the same letters as key, but possibly with different case. If found, return such a key. If not, return key.

When

Settingsare used in case-insensitive contexts, this helps preventing multiple occurences of the same key with different case:>>> s = Settings() >>> s.system.key1 = value1 >>> s.System.key2 = value2 >>> print(s) System: key2: value2 system: key1: value1 >>> t = Settings() >>> t.system.key1 = value1 >>> t[t.find_case('System')].key2 = value2 >>> print(t) system: key1: value1 key2: value2

-

as_dict()[source]¶ Return a copy of this instance with all

Settingsreplaced by regular Python dictionaries.

-

__missing__(name)[source]¶ When requested key is not present, add it with an empty

Settingsinstance as a value.This method is essential for automatic insertions in deeper levels. Without it things like:

>>> s = Settings() >>> s.a.b.c = 12

will not work.

Note

Methods update() and soft_update() are complementary.

Given two Settings instances A and B, the command A.update(B) would result in A being exactly the same as B would be after B.soft_update(A).