SCF Convergence Guidelines for ADF¶

The self-consistent field (SCF) method is the standard algorithm for finding electronic structure configurations within Hartree-Fock and density functional theory. SCF is an iterative procedure and can, depending on the situation at hand, sometimes be difficult to converge. Indeed, convergence problems occur in many different types of classes of chemical systems. These problems are most frequently encountered when the electronic structure exhibits a very small HOMO-LUMO gap, in systems with d- and f-elements with localized open-shell configurations, and in transition state structures with dissociating bonds. Finally, many SCF convergence problems are rooted in non-physical calculation setups, such as high-energy geometries or an inappropriate description of the electronic structure.

We advise to check and test the following list of options and aspects when encountering SCF convergence issues, starting from the most common and trivial ones:

- Ensure that the atomistic system under study is realistic. More specifically, check for the proper values of bond lengths, angles, and other internal degrees of freedom in the geometry. Unless specified otherwise, AMS expects atomic coordinates in Å. Also, when copying atomic structures into the graphical user interface, check that the imported structure is complete and that no atoms got lost during the process.

- The initial electronic structure is typically initialized as linear combinations of atomic configurations. However, a moderately (but not fully) converged electronic structure from, say, an SCF iteration conducted previously, likely represents a better initial guess already. Indeed in the next step of a geometry optimization, this moderately converged electronic structure information is reused as initial guess. The SCF iterations of the following geometry steps then usually converge even if the first electronic structure calculation does not. In the case of single-point calculations, the electronic structure needs to be read in via a manual restart.

- Assert that the correct spin multiplicity of the system is used. Open-shell configurations should be computed in a spin-unrestricted or, if necessary, a spin-orbit coupling formalism. It is needed to manually set the spin component (see the tutorial on spin coupling within an iron complex for more details). For non-converging open-shell systems, the evolution of the SCF errors during the iteration might also provide some insight into the problem. Strongly fluctuating errors may indicate an electronic configuration far away from any stationary point or an improper description of the electronic structure by the approximation used.

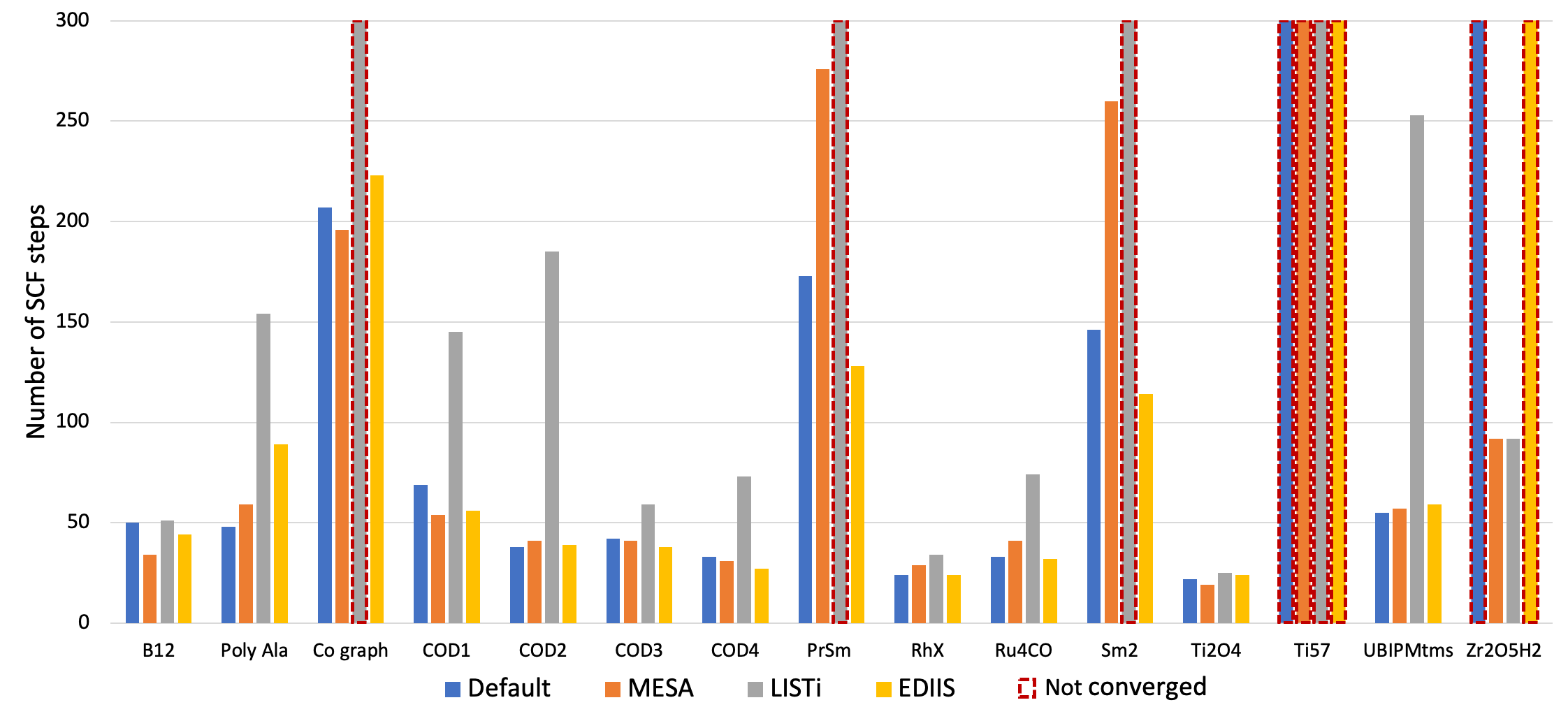

4. Change to a different SCF convergence acceleration method, like MESA, LISTi or EDIIS. To this end, examine at the documentation section for further details about the available SCF acceleration methods and the parameters controlling them. In the graphical user interface these options are available under Details → SCF and Details → SCF Convergence Details. The performance of these methods was tested for a variety of chemical systems that are difficult to converge. The corresponding results are depicted in Fig. 1 below and show that significant changes in the convergence behavior can be achieved with different accelerators.

Fig. 1 Number of SCF iterations needed to converge a series of different types of chemical systems with the ADIIS+SDIIS (default), MESA, LISTi, and EDIIS accelerator methods. Non-converged SCF iterations are depicted by dashed borders.

- The Augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) method is another alternative, though computationally more expensive, convergence acceleration method. ARH directly minimizes of the systems total energy as a function of the density matrix using a preconditioned conjugate-gradient method with a trust-radius approach. As shown in Fig. 2 below, ARH can in some situations be a viable alternative for difficult systems.

Fig. 2 Number of SCF iterations needed to converge a series of different types of chemical systems with the ADIIS+SDIIS (default) and ARH accelerators. Non-converged SCF iterations are depicted by dashed borders.

- Some parameters of the DIIS algorithm may also be changed manually. Note, that sometimes it is necessary to try multiple values and combinations of values until the desired outcome is achieved:

- Mixing denotes the fraction of the computed Fock matrix that is added when constructing the next guess for this matrix. More specifically, the Fock matrix resulting from the current guess for the electron density is combined with the corresponding matrices from multiple previous SCF iteration steps by the DIIS algorithm in order to construct the next guess. The mixing parameter controls the proportion of the computed Fock matrix in this linear combination, whereas a higher than the default value of 0.2 corresponds to a more aggressive acceleration, while lower value will lead to a more stable iteration and should be used for problematic cases.

- Mixing1 corresponds to the mixing parameter used in the very first SCF cycle. Its default of 0.2 should mainly be altered only in situation where one attempts to slowly converge the electronic structure starting from a restart file (see above).

- N is the number of DIIS expansion vectors used for the SCF acceleration (default N=10) by default. An input value smaller than 2 disables the DIIS. A higher number of expansion vectors (e.g. up to N=25) makes the SCF iteration more stable, while a smaller number makes it more aggressive.

- Cyc is the number of initial SCF iteration steps after which SDIIS will start (default Cyc = 5). An initial equilibration will take place in the cycles before, through which a higher value of Cyc causes a more stable computation.

- As an example, the following parameter values can be used as a starting point for a slow but steady SCF iteration of a difficult system:

SCF

DIIS

N 25

Cyc 30

End

Mixing 0.015

Mixing1 0.09

End

Besides the methods discussed above, other algorithms and techniques can be used to converge a problematic SCF calculations. However, as opposed the aforementioned options, the techniques listed below slightly alter the end result, which needs to be carefully tested:

- Electron smearing simulates a finite electron temperature by using fractional occupation numbers to distribute electrons over multiple electronic levels. This is particularly helpful to overcome convergence issues in larger systems exhibiting many near-degenerate levels. As electron smearing alters the systems total energy, the value of this parameter should be kept as low a possible, e.g. by using multiple restarts with successively smaller smearing values.

- The level shifting technique artificially raises the energy of unoccupied (virtual) electronic levels and can be used to overcome SCF convergence problems as well. It will, however, give incorrect values for properties involving virtual levels, such as excitation energies, response properties, and NMR shifts. Likewise, the electronic structure of metallic systems with a vanishing HOMO-LUMO gap might be inadequately described by this technique.