Gibbs Free Energy in Heterogeneous Catalysis¶

The accurate calculation of Gibbs Free Energy (\(\Delta\text{G}\)) is a cornerstone in understanding the thermodynamics of heterogeneous catalysis and constructing reliable reaction energy diagrams. However, transitioning from gas-phase molecules to species adsorbed on a solid surface introduces significant complexity in treating vibrational, translational, and rotational degrees of freedom. In this tutorial, we show how to compute these properties using AMS, focusing on the prototype system of \(\text{CO}_2\) adsorbed on Pt(111). We will walk through three distinct methodological approaches: full phonon analysis using periodic boundary conditions, \(\Gamma\)-point vibrational analysis (also known as the Harmonic Approximation), and the Partial Hessian approximation, which restricts the frequency calculation to a reduced group of atoms, typically the adsorbate atoms. By evaluating these three routes, this tutorial aims to provide practical insights into leveraging AMS’s tools to balance computational cost with chemical accuracy when describing the stability of reaction intermediates.

Specifically, this tutorial will show you how to:

Perform a full Phonon analysis to capture the complete vibrational component of the slab-adsorbate system, providing the most rigorous description of lattice and molecular vibrations.

Execute a vibrational analysis (\(\Gamma\)-point) to estimate free energy corrections using a molecular-like approach, ideal for rapid screening of adsorption stabilities.

Use the Partial Hessian approximation by isolating the vibrations of the adsorbed \(\text{CO}_2\) from the Pt(111) surface, effectively reducing computational cost but sacrificing accuracy for the adsorbate’s thermochemistry.

Through these three steps, you will learn to create the corresponding AMS input files and how to extract the necessary thermodynamic data from the output files.

Performing these calculations manually for each state is instructive and sometimes necessary for complex cases requiring specific user oversight, but it can be tedious for routine screening. To address this, the last two sections of this tutorial illustrate how to use the PESExploration module to automate the process. We will show how to use this feature to compute the full Gibbs Free Energy profile in a single run.

System Description & Computational Details¶

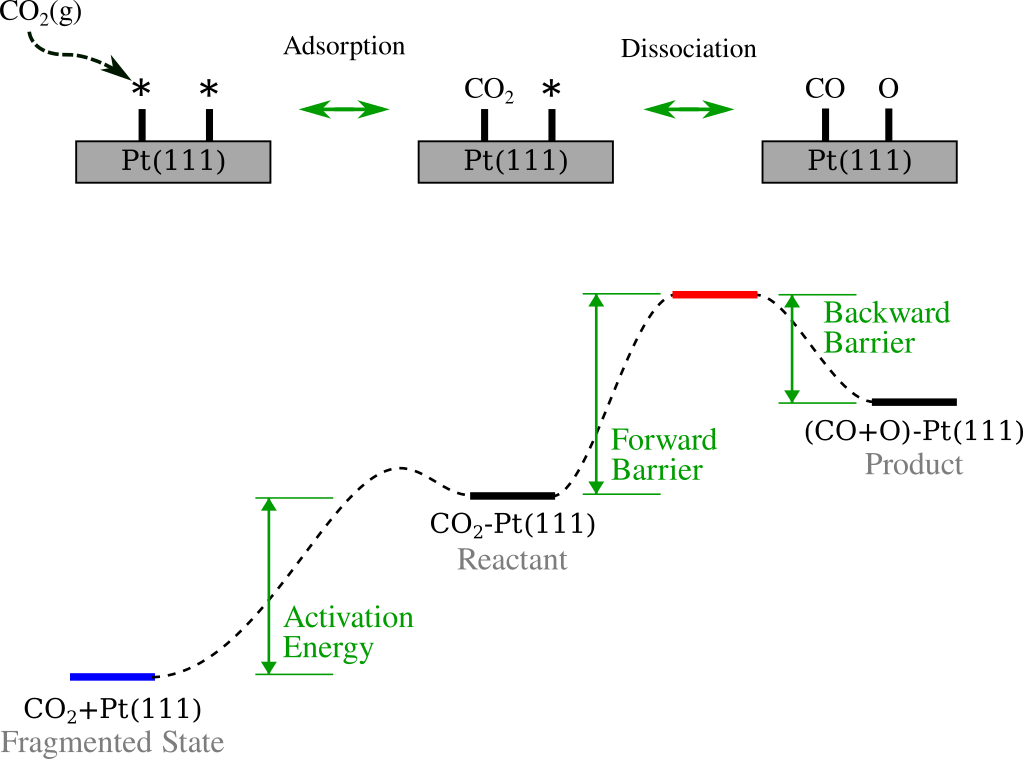

In this tutorial, we investigate the decomposition of \(\text{CO}_2\) on a Pt(111) surface. The reaction mechanism involves two steps:

Adsorption: \(\text{CO}_2\) from the gas phase adsorbs onto the Pt(111) surface. We refer to this adsorbed state as the reactant.

Dissociation: The adsorbed \(\text{CO}_2\) splits into adsorbed CO and O species. The final configuration is the product, and the process proceeds through a transition_state.

The figure below summarizes the process. The top panel illustrates the simplified mechanism: \(\text{CO}_2\) approaches the surface from the gas phase, adsorbs onto the Pt(111) slab, and subsequently dissociates into CO and O. The bottom panel maps these events onto a reaction energy profile, visually defining the key thermodynamic quantities we will calculate: the Activation Energy (the energetic cost to bring the molecule from the gas phase to the adsorbed reactant state), the Forward Barrier (energy required to reach the transition state from the reactant), and the Backward Barrier (energy required to reverse the reaction from the product).

Note

For simplicity, we assume the adsorption of \(\text{CO}_2\) (Gas \(\rightarrow\) Reactant) is a barrierless event. While detailed adsorption dynamics are crucial for kinetic modeling, they are outside the scope of this technical tutorial.

Here we chose the reactive force field (ReaxFF) engine in combination with the parameterization CHONSFPtClNi.ff, which has been specially designed to study the surface oxidation of Pt(111). In general, ReaxFF is highly efficient, allowing for rapid calculation of vibrational properties on large periodic systems.

Warning

We use ReaxFF here primarily for its speed to demonstrate the workflow. While ReaxFF is powerful, the reaction energies derived in this tutorial are illustrative and far from reality. For high-fidelity quantitative catalysis studies, one would typically employ electronic structure methods available in AMS through engines as e.g. BAND, Quantum Espresso, or DFTB. The procedure described here can be performed with any of these engines.

Setting up and running the calculations¶

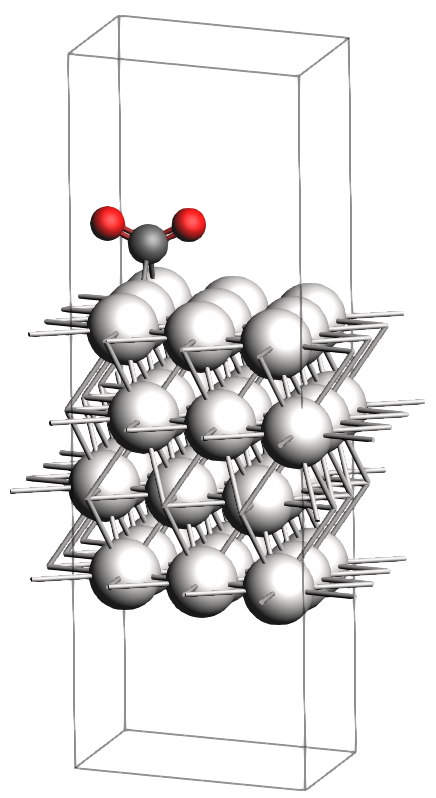

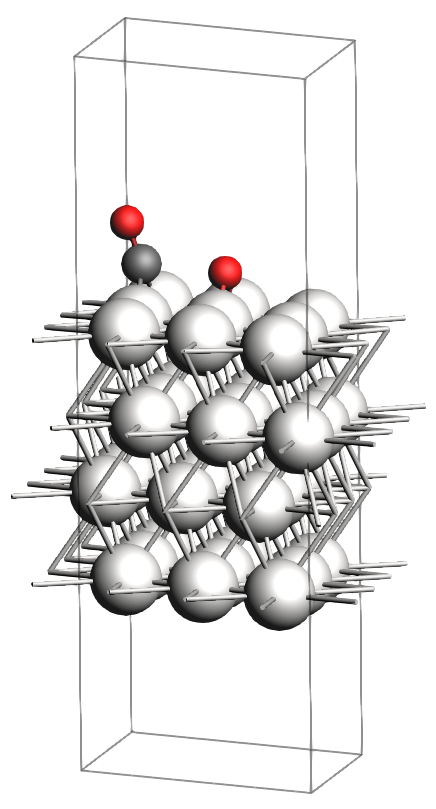

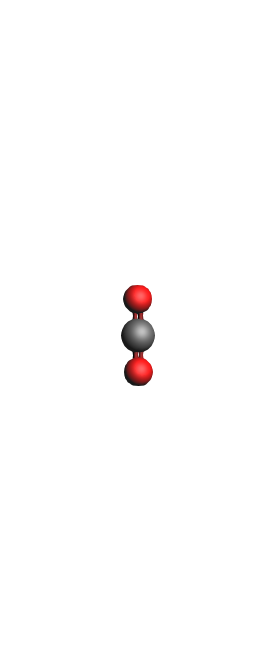

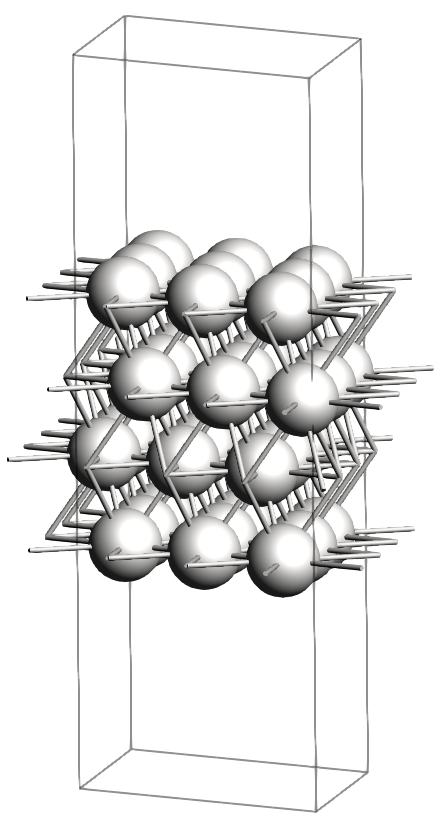

In the figures below, you will find images of the molecular structures of the chemical systems we need, along with the corresponding files for download in XYZ format:

These structures are already optimized using the same Force Field. In particular, as expected, the transition state has one single imaginary vibrational frequency, corresponding to the reaction coordinate that connects the reactant and product (which can be verified by an IRC calculation). Technically, the reaction involves a \(\text{CO}_2\) molecule adsorbed at a top site which splits into a CO and an O atom, both adsorbing onto bridge positions.

Take a look at those xyz files. Notice that they have two non-standard attributes that are understood by AMS: regions and lattice vectors.

See below the last 9 lines of the file reactant.xyz.

Notice that the regions are specified at the end of each atom line, and the lattice vectors are specified at the end using the prefix VEC.

The region surface will be used to specify which atoms belong to the slab, while molecule specifies which atoms should be considered active in the Partial Hessian approximation.

Though not used in this tutorial, regions can also be used to specify constraints, such as fixing the bottom layers of the slab.

Pt 6.46873537 6.95546929 1.23929151 region=surface

Pt 6.46886538 2.15431307 1.24049406 region=surface

Pt 7.85480350 4.55449971 1.24126856 region=surface

C 5.08298061 2.18108236 9.94736863 region=molecule

O 5.08432103 3.32848735 10.50195851 region=molecule

O 5.08179422 1.03897381 10.51165774 region=molecule

VEC1 8.31557575 0.00000000 0.00000000

VEC2 4.15778787 7.20149984 0.00000000

VEC3 0.00000000 0.00000000 20.00000000

Notice that the \(\text{CO}_2\) file does not have a lattice. This is intentional. It is necessary to treat the gas-phase molecule as isolated to correctly account for its rotational and translational contributions to the entropy, which are absent in the adsorbed phase.

Now, you can download the complete example script from this link CO2-Pt111.run and execute it as shown below.

Do not forget to download the xyz files into the same directory.

$ bash CO2+Pt111.run

The script will run all necessary calculations. However, throughout this tutorial, we will walk you through its different sections. Please execute the command above now. These calculations should take about 10 minutes on a standard laptop. Most of the time is spent on the phonon calculations, the rest of the tasks take only a few minutes or even seconds.

OK, let’s start …

Full Phonon analysis¶

The most rigorous way to calculate the free energy of solid-state systems is via Phonon analysis. The Gibbs Free Energy (\(G\)) is defined as \(G = H - TS = U + PV - TS\). For solid-state systems at standard pressures, the \(PV\) term is negligible compared to the internal energy (\(U\)) and entropic terms (\(TS\)). Therefore, we can approximate the Gibbs Free Energy as the Helmholtz Free Energy (\(F\)):

The input file section below sets up the calculation. The meanings of its blocks are as follows:

System: Defines the geometry (imported from

reactant.xyz).Task GeometryOptimization: Ensures we are at a local minimum before calculating frequencies.

Properties Phonons Yes: Triggers the calculation of the phonons.

Engine ReaxFF: Configures the parameters of the engine.

20AMS_JOBNAME=reactant_phonons "$AMSBIN/ams" > reactant_phonons.out << EOF

21 Task GeometryOptimization

22 Properties Phonons=Yes

23 System

24 GeometryFile reactant.xyz

25 End

26 Engine ReaxFF

27 ForceField CHONSFPtClNi.ff

28 EndEngine

29EOF

The output file (reactant_phonons.out) contains several technical details, but most importantly, the thermodynamic properties derived from the phonon calculation.

Look for the table “Thermodynamic properties from phonons”.

Since we are interested in the reaction at 400 K, locate the row corresponding to Temperature(K) = 4.000000E+02.

The column Free Energy(Hartree) corresponds to the Helmholtz energy (\(F\)), which we use as our approximation for \(G\).

========================================

Thermodynamic properties from phonons

========================================

Zero-point Energy (hartree) 0.05760994

Zero-point Energy (eV) 1.56764611

=============================================================================================

Temperature(K) Internal energy(Hartree) Entropy(kB) Free Energy(Hartree) Specific Heat(kB)

0.000000E+00 5.760994E-02 0.000000E+00 5.760994E-02 0.000000E+00

1.000000E+00 5.760994E-02 8.376922E-04 5.760994E-02 3.795979E-03

...

3.990000E+02 1.647318E-01 1.904671E+02 -7.593468E-02 1.097737E+02

4.000000E+02 1.650795E-01 1.907419E+02 -7.653829E-02 1.097921E+02

4.010000E+02 1.654272E-01 1.910161E+02 -7.714277E-02 1.098104E+02

...

9.990000E+02 3.781614E-01 2.933058E+02 -5.497552E-01 1.136389E+02

1.000000E+03 3.785212E-01 2.934195E+02 -5.506842E-01 1.136415E+02

=============================================================================================

...

=====================

CALCULATION RESULTS

=====================

Energy (hartree) -7.83513196

...

The energy contribution from the phonons calculation in AMS (the “Free Energy” column in the table) does not include the total electronic energy of the system. It only includes vibrational corrections (ZPE and thermal).

To compare with results from other methods described below, we must calculate \(G_{total} = E_e + F_{phonons}\), where \(E_e\) is the electronic energy from the engine.

Its value can be obtained from the output file in the highlighted line that starts with Energy (hartree) after the CALCULATION RESULTS section.

In this tutorial, we will use eV as the preferred unit of energy. Be careful to convert the Free Energy correction from Hartree to eV. For this particular case:

This procedure (Optimization + Phonons) must be repeated for the transition_state, product, and surface.

You can do this by replacing the word reactant with transition_state, product, and surface, respectively, in the input file section shown above.

Check the downloaded script for the full implementation. Then, collect all values of \(E_e\) and \(G\), we will analyze them later.

Notice that this phonon calculation does not apply to the isolated \(\text{CO}_2\) molecule. Its free energy must be calculated using the molecular vibrational analysis (Ideal Gas Rigid Rotor Harmonic Oscillator) described in the next section.

\(\Gamma\)-point Vibrational Analysis¶

As you may have appreciated, calculating full phonons is computationally expensive. Running the provided script, the phonon calculations consumed more than 99% of the computational time. This cost often makes phonon analysis unaffordable for routine screening. Most engines calculate phonons using a finite difference approximation on a supercell, which scales poorly with system size. Therefore, a sufficient approximation is often to calculate vibrations only at the \(\Gamma\)-point (the center of the Brillouin zone).

In the input file, this is triggered by Properties NormalModes=Yes.

Crucially, we define the temperature of interest using Thermo Temperatures=400.0.

57AMS_JOBNAME=reactant "$AMSBIN/ams" > reactant.out << EOF

58 Task GeometryOptimization

59 Properties NormalModes=Yes

60 Thermo Temperatures=400.0

61 System

62 GeometryFile reactant.xyz

63 End

64 Engine ReaxFF

65 ForceField CHONSFPtClNi.ff

66 EndEngine

67EOF

In the output (reactant.out), look for the Statistical Thermal Analysis section.

AMS provides a breakdown of:

Entropy: The entropic contribution (\(S\)).

Internal Energy: Thermal corrections to the energy (\(U\)).

Gibbs free energy: The final target value (\(G\)).

============================

Statistical Thermal Analysis *** ideal gas assumed ***

============================

...

Temp Transl Rotat Vibrat Total

---- ------ ----- ------ -----

400.00 Entropy (cal/mol-K): 0.000 0.000 371.654 371.654

Nuclear Internal Energy (kcal/mol): 0.000 0.000 101.541 101.541

Constant Volume Heat Capacity (cal/mol-K): 0.000 0.000 214.407 214.407

(c) Constant Volume Heat Capacity (cal/mol-K): 0.000 0.000 185.131 185.131

Summary of energy terms

hartree eV kcal/mol kJ/mol

-------------------- ----------- ---------- -----------

Energy from Engine: -7.835131964120705 -213.2048 -4916.62 -20571.14

Nuclear Internal Energy: 0.161816248193982 4.4032 101.54 424.85

(c) Nuclear Internal Energy: 0.142120666965567 3.8673 89.18 373.14

Internal Energy U: -7.673315715926722 -208.8015 -4815.08 -20146.29

pV/n = RT: 0.000000000000000 0.0000 0.00 0.00

Enthalpy H: -7.673315715926722 -208.8015 -4815.08 -20146.29

-T*S: -0.236907582306557 -6.4466 -148.66 -622.00

(c) -T*S: -0.219336266121665 -5.9684 -137.64 -575.87

Gibbs free energy: -7.910223298233278 -215.2481 -4963.74 -20768.29

Note that for the reactant (and the other periodic systems like the surface or product), AMS automatically detects the periodicity. Consequently, the Translational and Rotational contributions to the Entropy and Internal Energy are set to zero, as the slab cannot rotate or translate. The \(PV\) term is also zeroed out.

This procedure (Optimization + Vibrational Analysis) must be repeated for the transition_state, product, co2, and surface. Check the full script for details.

Unlike the Phonon analysis, here we also calculate the \(\text{CO}_2\) free energy using this method.

In contrast, for the isolated \(\text{CO}_2\) molecule (co2.out), these translational and rotational terms will are non-zero and contribute significantly to the gas-phase free energy.

Collect all values of \(G\) for later analysis. For the reactant case shown above: \(G = -215.2481 \,\text{eV}\)

\(\Gamma\)-point Vibrational Analysis & Partial Hessian Approximation¶

Calculating the Hessian for the entire surface slab is often unnecessary. The metal atoms in the bulk and surface are significantly heavier than the adsorbate, and their vibrations are often effectively decoupled from the reaction coordinate. The Partial Hessian Approximation drastically reduces computational cost by calculating second derivatives of the energy only for a selected subset of active atoms. In more complex cases, you can extend the active region to include specific surface atoms if their vibrations are strongly coupled to the adsorbate.

The input setup is nearly identical to the \(\Gamma\)-point analysis. We simply add a specification for the active region.

In our case, we defined molecule as the active region (SelectedRegionForHessian=molecule).

121AMS_JOBNAME=reactant_PH "$AMSBIN/ams" > reactant_PH.out << EOF

122 Task GeometryOptimization

123 Properties NormalModes=Yes SelectedRegionForHessian=molecule

124 Thermo Temperatures=400.0

125 System

126 GeometryFile reactant.xyz

127 End

128 Engine ReaxFF

129 ForceField CHONSFPtClNi.ff

130 EndEngine

131EOF

Below is the important section of the output file. Observe that the translational and rotational contributions are zero, as expected. Most notably, the vibrational contributions are much smaller than in the full analysis because we are ignoring the bulk lattice modes.

============================

Statistical Thermal Analysis *** ideal gas assumed ***

============================

...

Temp Transl Rotat Vibrat Total

---- ------ ----- ------ -----

400.00 Entropy (cal/mol-K): 0.000 0.000 15.972 15.972

Nuclear Internal Energy (kcal/mol): 0.000 0.000 15.810 15.810

Constant Volume Heat Capacity (cal/mol-K): 0.000 0.000 11.224 11.224

(c) Constant Volume Heat Capacity (cal/mol-K): 0.000 0.000 9.806 9.806

Summary of energy terms

hartree eV kcal/mol kJ/mol

-------------------- ----------- ---------- -----------

Energy from Engine: -7.835131964120701 -213.2048 -4916.62 -20571.14

Nuclear Internal Energy: 0.025195608038802 0.6856 15.81 66.15

(c) Nuclear Internal Energy: 0.024256233113602 0.6600 15.22 63.68

Internal Energy U: -7.809936356081900 -212.5192 -4900.81 -20504.99

pV/n = RT: 0.000000000000000 0.0000 0.00 0.00

Enthalpy H: -7.809936356081900 -212.5192 -4900.81 -20504.99

-T*S: -0.010181400480265 -0.2771 -6.39 -26.73

(c) -T*S: -0.009126151883620 -0.2483 -5.73 -23.96

Gibbs free energy: -7.820117756562165 -212.7963 -4907.20 -20531.72

This procedure (Optimization + Vibrational Analysis with Partial Hessian) must be repeated for the transition_state and product. Check the full script for details, and collect all values of \(G\) for later analysis. For the reactant case: \(G = -212.7963 \,\text{eV}\).

For the \(\text{CO}_2\) molecule, we don’t need a new calculation. Since we treat the whole molecule, the partial Hessian is equivalent to the full Hessian.

Results¶

The table below summarizes the calculated Gibbs Free Energies and the resulting barrier heights for the three methods.

T = 400 K |

Gibbs Free Energy (eV) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Energy (eV) |

Phonons |

Full Hessian |

Partial Hessian |

|

Reactant |

-213.2049 |

-215.2482 |

-215.2482 |

-212.7963 |

Transition State |

-209.6474 |

-212.0116 |

-211.8783 |

-209.3745 |

Product |

-210.3997 |

-212.8065 |

-212.6857 |

-210.1851 |

\(\text{CO}_2\) |

-19.3909 |

-19.1666 |

-19.1666 |

-19.1666 |

surface |

-194.7569 |

-197.3883 |

-197.2092 |

-194.7569 |

Forward Barrier |

3.5575 |

3.2760 (0.0%) |

3.3699 (2.9%) |

3.4218 (4.4%) |

Backward Barrier |

0.7523 |

0.7949 (0.0%) |

0.8074 (1.6%) |

0.8106 (2.0%) |

Activation Energy |

0.9429 |

1.2673 (0.0%) |

1.1276 (11.0%) |

1.1272 (11.0%) |

There are two important points to clarify in this table: Firstly, notice that for the \(\text{CO}_2\) molecule, the Gibbs Free Energy is identical across all three columns. This is because phonons are not applicable to isolated molecules, and the Partial Hessian (when applied to the entire molecule) is mathematically equivalent to the Full Hessian. And secondly, for the surface in the Partial Hessian column, the Gibbs Free Energy (\(-194.7569\) eV) is identical to the raw electronic Energy. This occurs because the Partial Hessian approach ignores the vibrations of the surface atoms. Consequently, the surface is treated as a static environment with zero entropy and zero ZPE.

Regarding the accuracy of the methods, the table confirms that the Partial Hessian approximation introduces a larger error than the Full Hessian when compared to the benchmark Phonon calculations (4.4% vs 2.9% for the forward barrier). This is expected, as the Partial Hessian neglects the explicit coupling between the adsorbate and the surface lattice vibrations. However, more important are the physical insights revealed by the Gibbs Free Energy corrections. When we shift from raw electronic energy to free energy, the Activation Energy for adsorption increases significantly (from 0.94 eV to 1.27 eV), implying that the adsorption probability is lower than purely energetic models would suggest. In contrast, the Forward Barrier for dissociation decreases (from 3.56 eV to 3.28 eV), making the C-O bond breaking kinetically more likely, while the Backward Barrier increases slightly, making the recombination step more difficult.

Energy Landscape Refinement - \(\Gamma\)-point Vibrational Analysis¶

AMS offers a dedicated task called PESExploration which streamlines the calculation of reaction profiles.

Instead of running separate calculations for each state and manually collecting data, the Job LandscapeRefinement computes the entire profile in a single run.

The corresponding input file is shown below. The meanings of its blocks are as follows:

Systems: We define

System REACT,System PROD, andSystem TS. Note that the transition state definition links the reactant and product:System TS ts=yes reactant=REACT product=PROD.LandscapeRefinement: The keyword

GenerateFragments Yesautomatically identifies the adsorbate and surface fragments from the input geometries.StatesAlignment: We use

ReferenceRegion surfaceto tell AMS which atoms constitute the catalytic surface. TheDistanceDifference=0.5parameter is crucial here; since the surface atoms relax slightly differently in each state, this threshold (in Angstroms) allows AMS to correctly identify that the underlying surface is chemically identical across all states despite small geometric variations.Thermo Temperatures: As before, we set the temperature to 400.0 K.

161AMS_JOBNAME=landscape "$AMSBIN/ams" > landscape.out << EOF

162 Task PESExploration

163 Thermo Temperatures=400.0

164 PESExploration

165 Job LandscapeRefinement

166 LandscapeRefinement GenerateFragments=Yes

167 StatesAlignment ReferenceRegion=surface DistanceDifference=0.5

168 End

169 System REACT

170 GeometryFile reactant.xyz

171 End

172 System PROD

173 GeometryFile product.xyz

174 End

175 System TS ts=Yes reactant=REACT product=PROD

176 GeometryFile transition_state.xyz

177 End

178 Engine ReaxFF

179 ForceField CHONSFPtClNi.ff

180 EndEngine

181EOF

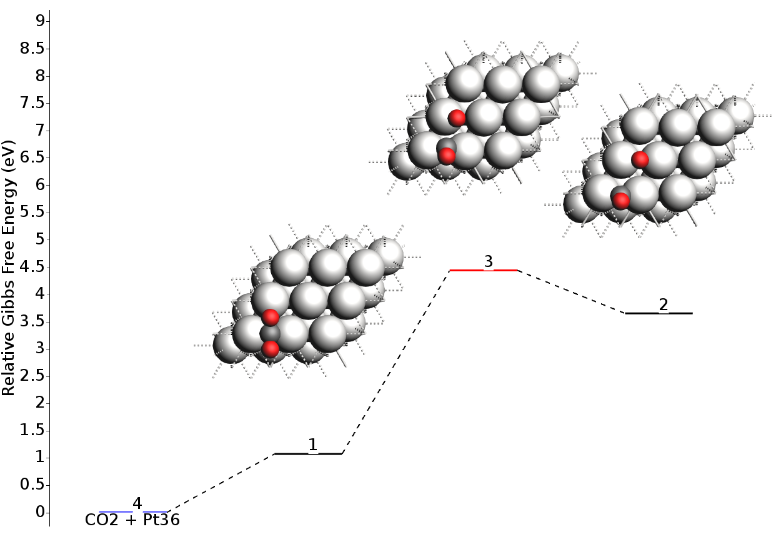

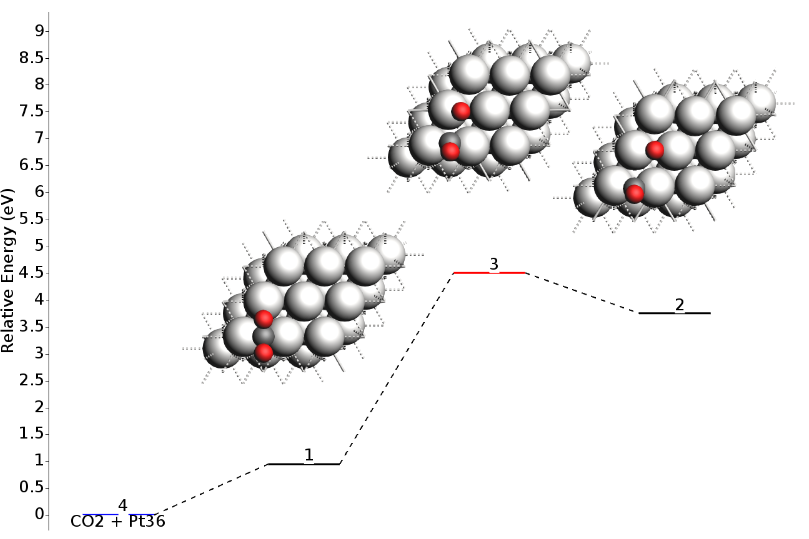

This single input generates the full Energy Landscape, which can be visualized using the AMSmovie command.

The barrier heights obtained here are identical to those calculated “molecule-by-molecule” in the previous sections.

$ amsmovie landscape.results

You should see something like this:

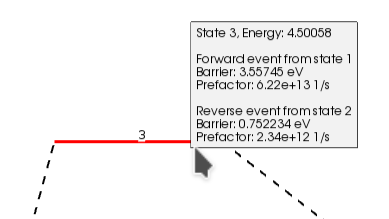

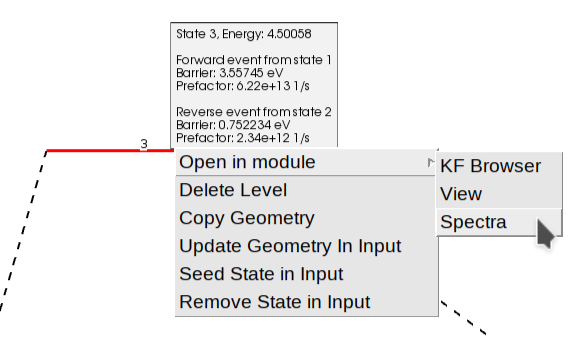

You can see the size of the barrier (Forward/Backward) by passing the mouse over the line that represents the transition state (red line). Notice that the values shown in AMSmovie are the same ones we found using the individual calculations in the table above:

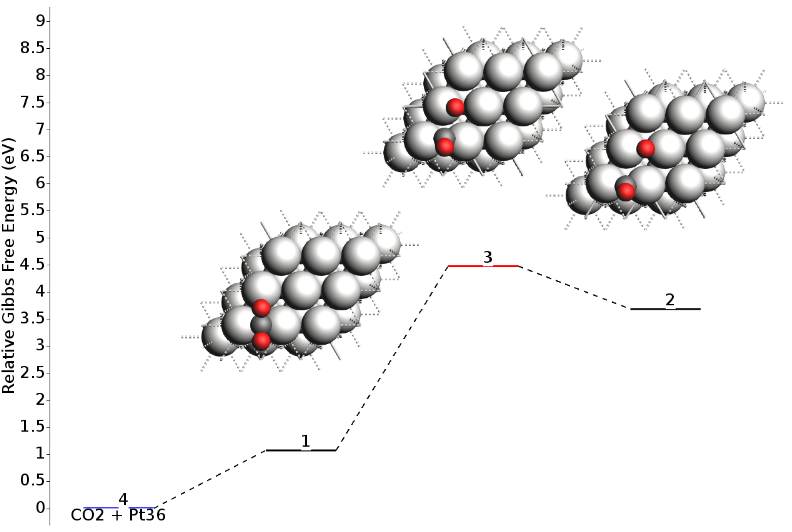

From the AMSmovie menu bar, you can select Gibbs Free Energy:

The reaction profile will update to show the Gibbs Free Energy:

In addition to seeing the energy barriers by passing the mouse over different states, you can right-click on top of it to open a context menu. This allows you to view the structure, the calculated properties (“Open in module” -> “View”), or inspect the vibrational spectrum (“Open in module” -> “Spectra”) to analyze vibrational modes and frequencies in detail.

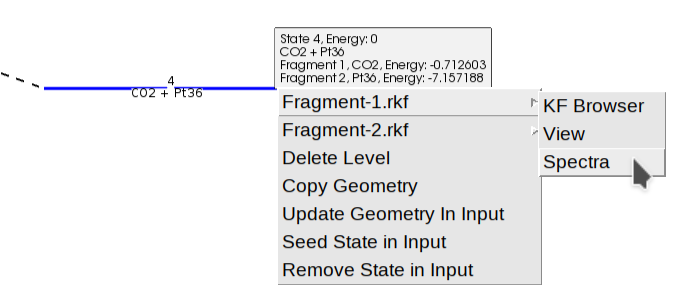

As we mentioned before, the option LandscapeRefinement GenerateFragments=Yes triggers the calculation of fragments.

One fragment represents the surface and the other represents the molecule. Their definition is based on the region surface.

The atoms outside of the region surface form the first fragment (\(\text{CO}_2\)), and the atoms inside that region form the second fragment (the surface).

The generation of fragments involves the geometry optimization of each fragment independently.

You can view the individual energies of the fragments by hovering over the fragmented state (blue line), or by right-clicking to access the “View” or “Spectra” options for a specific fragment (e.g., “Fragment-1.rkf” for the \(\text{CO}_2\)).

Energy Landscape Refinement - \(\Gamma\)-point Vibrational Analysis & Partial Hessian Approximation¶

Finally, we can combine the PESExploration workflow with the cost-saving Partial Hessian approximation.

The input is almost identical to the previous section, with one key addition: Properties SelectedRegionForHessian=molecule.

Here, molecule refers to the region defined for the \(\text{CO}_2\) adsorbate.

This tells AMS to calculate vibrational normal modes only for the adsorbate atoms, ignoring the surface modes.

The resulting energy landscape (shown below) is visually very similar to the full vibrational analysis, and the numerical values match exactly with the Partial Hessian results presented in the summary table above. This approach offers an optimal balance of precision and computational cost.

187AMS_JOBNAME=landscape_PH "$AMSBIN/ams" > landscape_PH.out << EOF

188 Task PESExploration

189 Properties SelectedRegionForHessian=molecule

190 Thermo Temperatures=400.0

191 PESExploration

192 Job LandscapeRefinement

193 LandscapeRefinement GenerateFragments=Yes

194 StatesAlignment ReferenceRegion=surface DistanceDifference=0.5

195 End

196 System REACT

197 GeometryFile reactant.xyz

198 End

199 System PROD

200 GeometryFile product.xyz

201 End

202 System TS ts=Yes reactant=REACT product=PROD

203 GeometryFile transition_state.xyz

204 End

205 Engine ReaxFF

206 ForceField CHONSFPtClNi.ff

207 EndEngine

208EOF

This is the result you would get for the energies:

And this is the result in terms of Gibbs free energies:

Conclusions & Next Steps¶

In this tutorial, we have explored the calculation of Gibbs Free Energies for catalytic reactions on surfaces.

You have learned that while full Phonon calculations provide the highest accuracy by treating the complete lattice dynamics, they are often computationally prohibitive.

The Partial Hessian Approximation emerged as a powerful alternative, yielding relative barrier heights with errors of less than 5% compared to the full phonon treatment, but at a fraction of the time.

We also demonstrated how to automate this process using the PESExploration task, allowing you to generate comprehensive reaction energy profiles in a single run.

Armed with these thermodynamic data, a natural next step in your research might be to perform a microkinetic analysis to determine reaction rates and turnover frequencies under realistic operating conditions. You can explore AMS’s microkinetics MKMCXX or the pyZacros modules, to take your static energy landscapes into the realm of dynamic catalysis modeling.