Band Structure and COOP¶

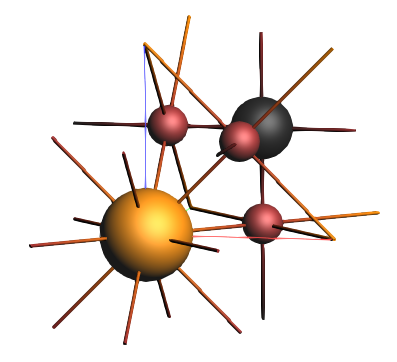

Using the perovskite CsPbBr3 as an example, this BAND tutorial illustrates how the analysis of density of states (DOS) and crystal-orbital overlap populations (COOP) provides insights about the nature of chemical bonding within crystalline materials. This also reveals starting points for a systematic tuning of the band gap in such crystals which is of paramount importance for photoelectric and optoelectronic applications. The tutorial is largely based on the following publication:

M. G. Goesten and R. Hoffmann Mirrors of Bonding in Metal Halide Perovskites, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12996-13010 (2018).

The following seminal paper describes in more detail how to extend chemical concepts into the field of solid state physics:

R. Hoffmann How Chemistry and Physics Meet in the Solid State, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 26, 846-878 (1987).

Note

Accurate band gap calculations can be far from trivial problems even within the framework of DFT. Band gaps from semi-local density functional approximations like LDA or GGA are generally underestimated due to spurious artifacts such as the electronic self-interaction error. More accurate results can be obtained from non-local approaches like hybrid DFT or GW methods, but these methods have much higher computational costs. A recent performance assessment study with BAND examines the accuracy of several density functional approximations for the prediction of the band gaps in various crystals.

The original study relies on the meta-GGA functional SCAN, which the authors considered to be a reasonable trade-off between accuracy or computational costs.

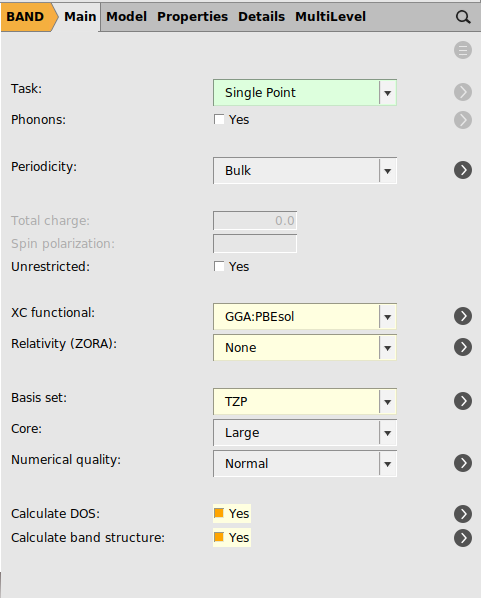

In contrast, this tutorial will – for the sake of efficiency – employ the GGA functional PBEsol, a smaller basis set, and a frozen core treatment.

While more approximate, this approach still yields to the same qualitative results as the original work.

An AMSinput file with the same settings as used by Goesten and Hoffmann can be obtained here.

Step 1: Preparations¶

We first create a separate folder for all calculations of this tutorial

followed by the preparation of the model structure of the perovskite crystal. In principle such an atomistic model is readily available from structure databases like materialsproject.

To speed up the calculations required in this tutorial, we provide two structures whose geometries were optimized with (SR) and without (NR) a scalar relativistic treatment. These structures can be obtained here:

CsPbBr3_NR.xyzCsPbBr3_SR.xyzNote

In custom applications, you might need to optimize the structures first. This also include optimizing the lattice parameters.

CsPbBr3_NR.xyz and click OKThe editor should now show the atoms of the first unit cell as well as the lattice vectors:

Step 2: Calculations¶

With the file CsPbBr3_NR.xyz loaded as structure in the molecular editor

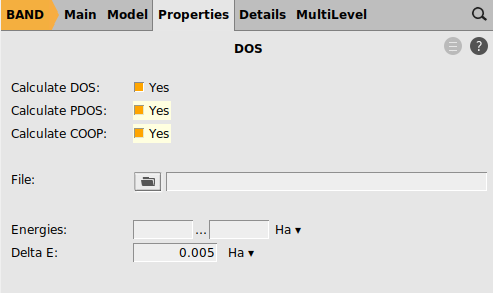

To enable the COOP calculation:

button next to PDOS

button next to PDOS

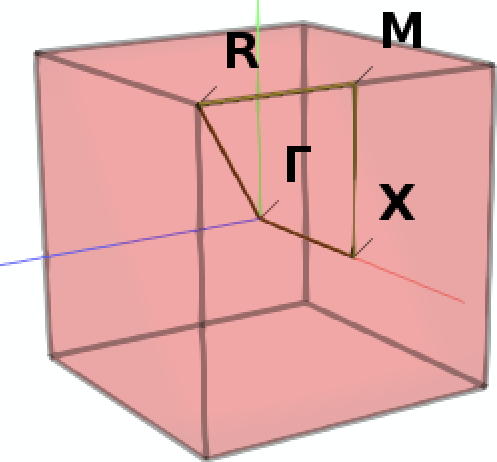

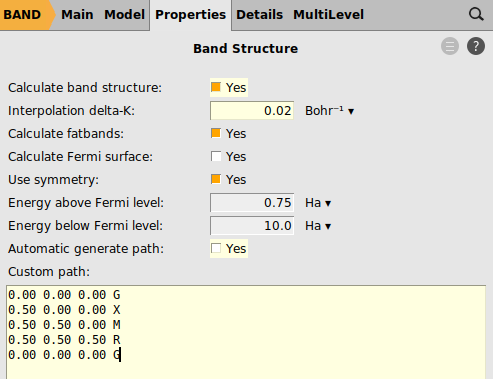

Next we define a specific path through the Brillouin zone along which we want to sample the band structure: From the center Γ we move first to the center X of a facet of the cubic Brillouin zone, then to M in the middle of one of its vertices, then to the corner R to finally return to Γ.

Note

A path consisting of multiple disconnected segments can be defined by leaving an empty line between each block defining a segment

CsPbBr3_NR.amsNext, load the structure in the file CsPbBr3_SR.xyz and enable the scalar relativistic treatment in the Main panel:

CTRL+A and pressing delete)CsPbBr3_SR.xyzApart from that, set exactly the same options as for the non-relativistic calculation. This is most easily done as described above – by first filling in the right settings for one molecule, deleting that molecule, loading a new molecule, and changing the single setting (Relativity) that is different between the two calculations.

Save this second job, then run both calculations:

CsPbBr3_SR.amsStep 3: Inspecting the Band Structure¶

After completion of both calculations

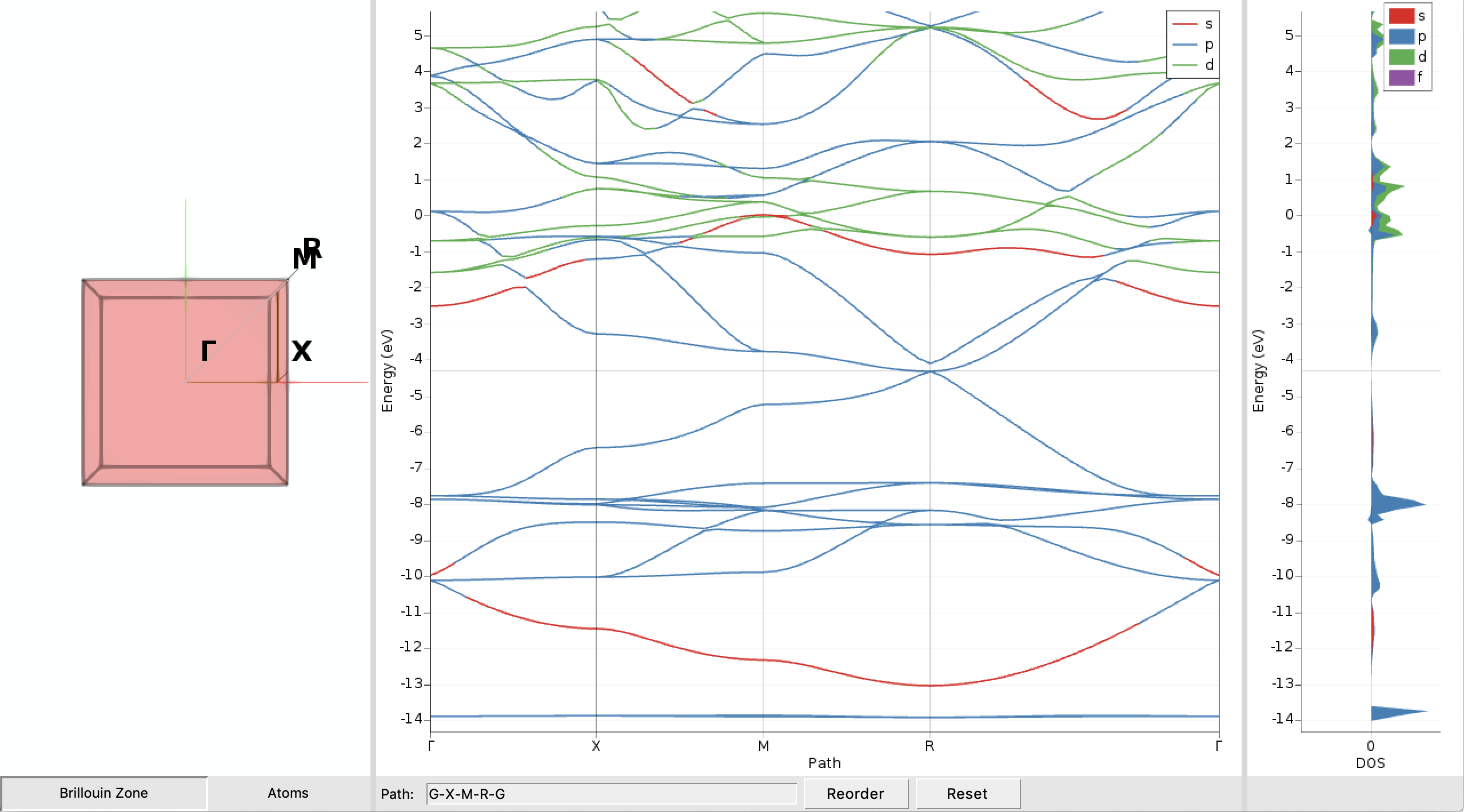

CsPbBr3_NR in AMSjobsAfter a few seconds you should see a plot of the band structure:

We immediately see that the CsPbBr3 perovskite exhibits no band gap in our nonrelativistic description as the valence and conduction band touch at the Fermi-level (the thin horizontal grey line) at the point R in the Brillouin zone. The band gap and the Fermi level can be examined in more detail by doing the following:

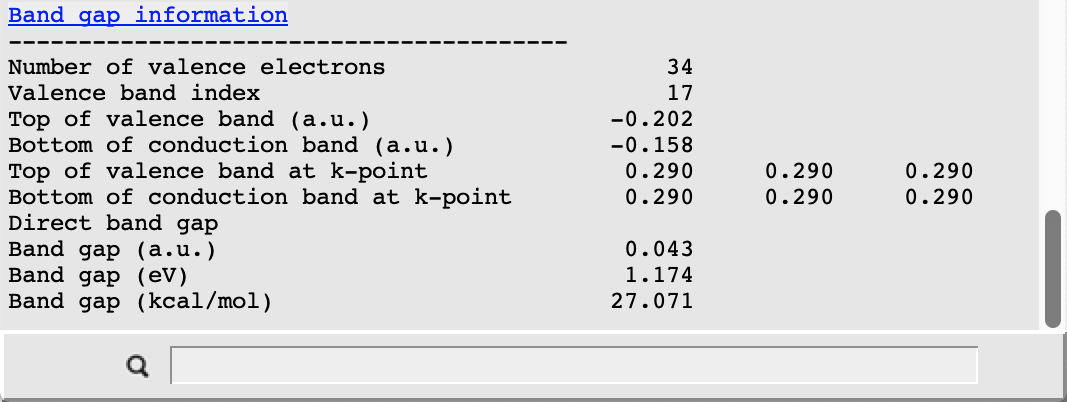

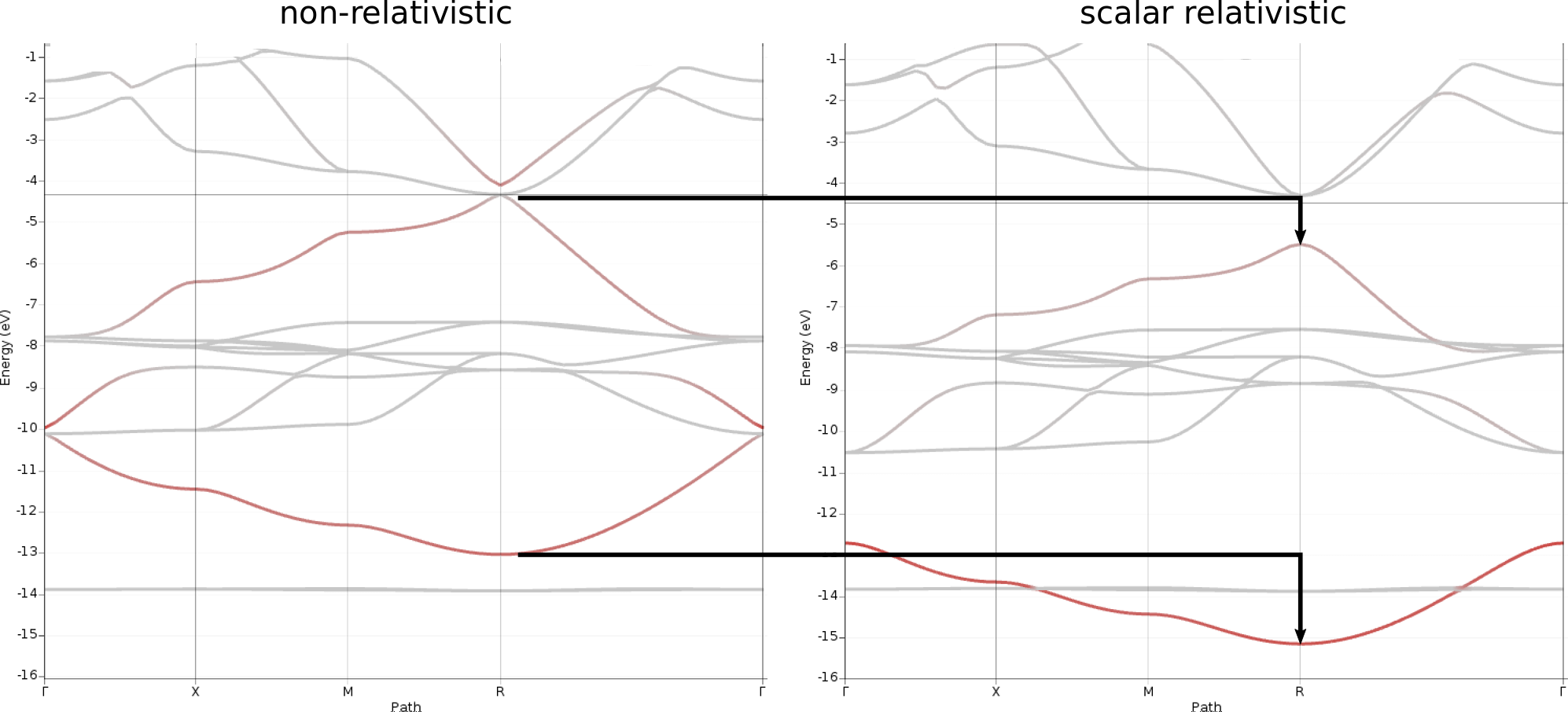

The picture changes when looking at the corresponding results from the scalar relativistic calculation:

In this case the valence band at R is separated from the conduction band by about 1.2 eV. This value is smaller than the result obtained in the original study due to the different choice of the density functional approximation. In both cases we nonetheless observe a clear effect of the scalar relativistic description: the highest occupied band is lowered in energy and so is another occupied band near the bottom of our plot. Also note that, due to the presence of Pb, a spin-orbit coupling description should be used for relativistic effects when aiming to reproduce experimental results.

In the following we will examine the atomic orbital contributions to the two shifted bands mentioned above. At this point we can make the following assumptions:

The bands arising from orbitals of the heavy elements Cs and Pb will be most affected by the scalar relativistic correction. Such relativistic effects on heavy atoms are indeed encountered quite frequently.

The Cs centers in the perovskite crystal will be simple cations and thus their orbitals will not participate in any chemical bonding and only contribute to non-dispersed bands

To visualize the contributions from Pb s levels, do the following steps for both bandstructures, relativistic and non-relativistic:

-16 and Maximum value to 0The resulting plots now highlight those band segments with significant contributions from the Pb 6s orbital.

From these plots the following observations can be made:

Two bands are mainly affected by the relativistic treatment as they are both lowered in energy by 1-2 eV

These two bands correspond to those with the highest contributions from the Pb6s orbitals

The Pb6s contribution is about equal for upper and lower band in the non-relativistic case, while Pb6s contributes more to the lower band in the relativistic case

For both, relativistic and non-relativistic band structures, we find that the two Pb6s bands roughly appear as vertically mirrored images of each other along the path Γ → X → M → R → Γ

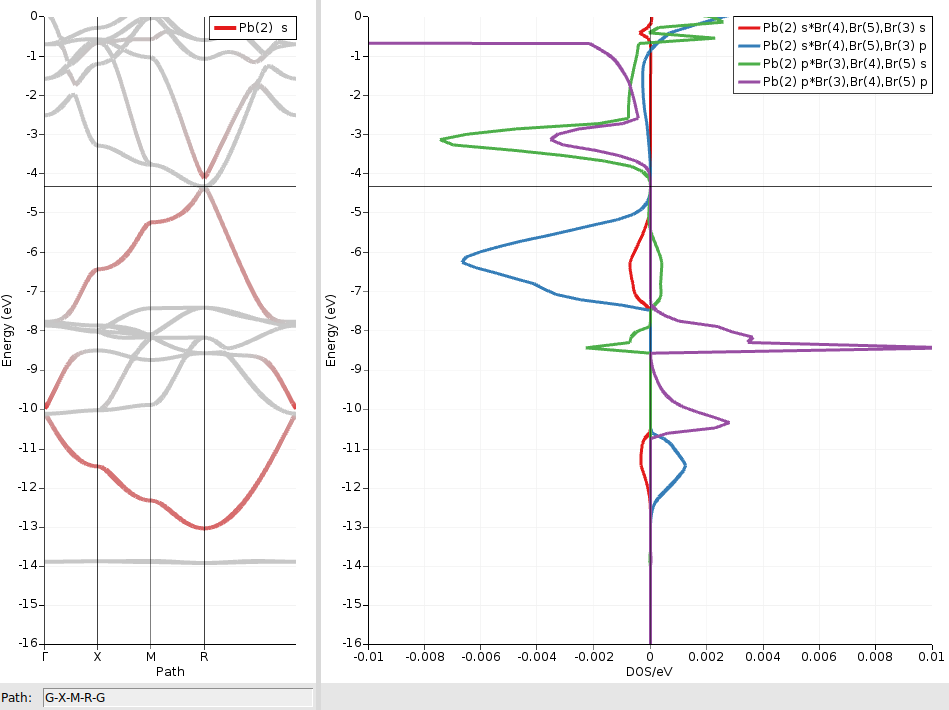

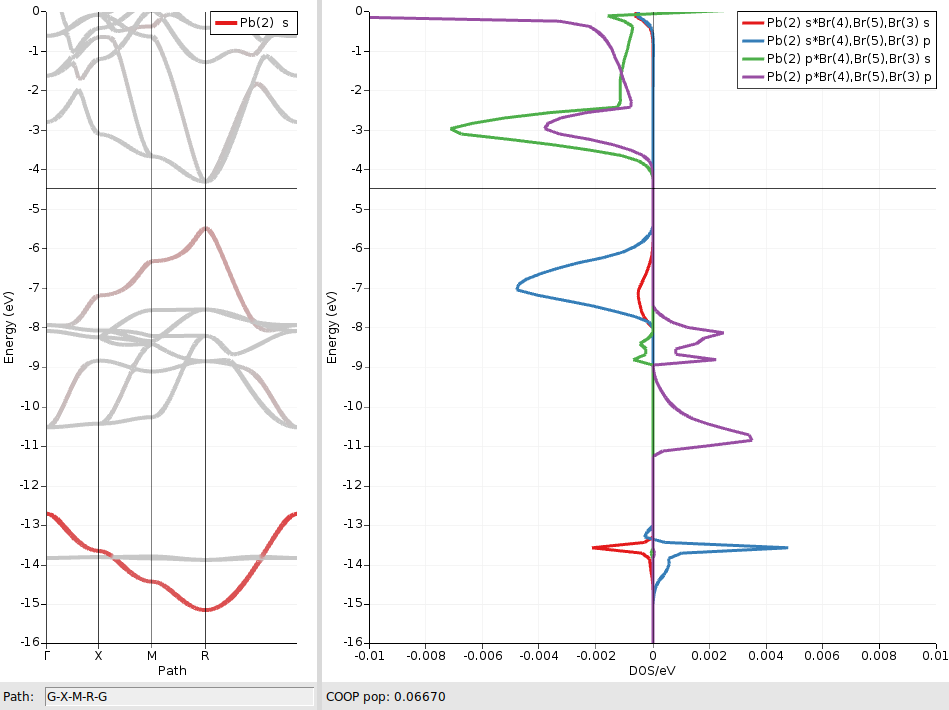

We will use crystal-overlap orbital populations (COOP) to examine these two bands further. A COOP is defined between a pair of orbitals (or pair of orbital shells) and directly indicates the bonding character of those crystal orbitals at different energies. In the CsPbBr3 crystal each Pb atom has six Br centers as nearest neighbors. We therefore focus on COOP plots between Pb and Br orbital shells, which can be obtained as follows:

We repeat the above steps also for the combinations Pbs/Brp, Pbp/Brs, and Pbp/Brp :

as well as for the corresponding pairs in the relativistic case:

Remark: graph editing options can be accessed by clicking DOS → Options… or by clicking outside of the plot, so in the area around the left or bottom axes. This allows one to adjust the line width of a curve, for example. The relative sizes of the individual graphs in the window can be changed if one drags the line that is in between these graphs with a mouse.

We see that the two shifted bands are mainly formed from bonding and antibonding Pb6s/Br4p linear combinations, respectively. The much smaller contributions from antibonding Pbs/Brs orbitals (red curves) can be ignored here.

Interpretation of Results¶

These results allow us now to rationalize our previous observations:

Why are only the 6s bands shifted by the relativistic treatment and all others not?

The Pb6s orbital is lowered in energy by the relativistic treatment and consequently all bands this orbital contributes to. When applying a relativistic treatment, s orbitals are energetically lowered and contracted more than p orbitals, while d and f orbitals are raised and expanded. The relative amount of scalar relativistic effects on p orbitals compared to s levels is thus smaller and can lead to basically unaffected bands as in results obtained here. These relativistic effects are understood well in literature. See for example the following publication:

Baerends, W. H. E. Schwarz, P. Schwerdtfeger and J. G. Snijders Relativistic atomic orbital contractions and expansions: magnitudes and explanations, J. Phys. B, 23, 3225-3240 (1990).

Why do the relative contributions of 6s in the two shifted bands change when going from the non-relativistic to the relativistic case?

This effect can be explained with basic molecular orbital theory. When two levels interact and form linear combinations, the lower linear combination will have more contributions from the lower level, while the higher one will be formed to a larger extend by the higher level. In the scalar relativistic case the 6s orbitals are essentially lowered with respect to all other levels and will therefore contribute more to the lower band in this case.

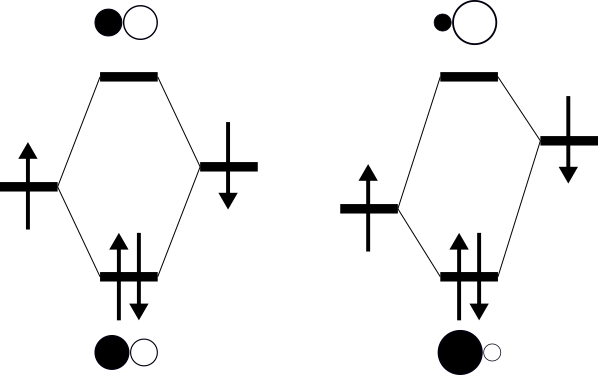

Why do the two bands appear as vertical mirror images of each other?

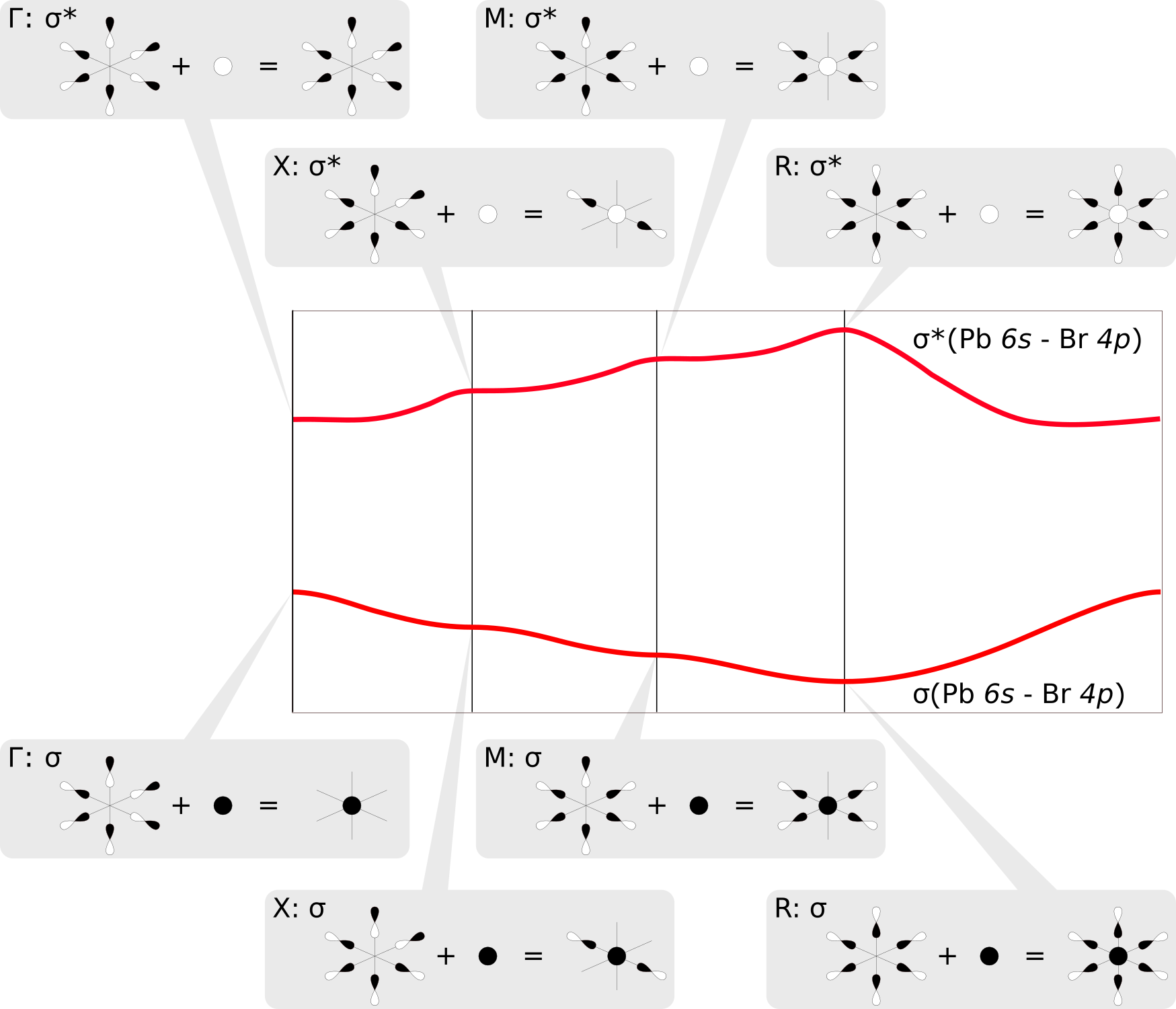

The COOP plots above clearly indicate that the two shifted bands are formed by σ-type bonding and antibonding Pb6s/Br4p linear combinations, respectively. We find that each octahedral PbBr6 unit in the CsPbBr3 crystal has three Br centers that are located in neighboring unit cells. At the sampled high symmetry points of the Brillouin zone [e.g. X at (0.5 0.0 0.0), see above], the resulting Bloch functions assume values of -1, thus changing the sign of the p orbitals of Br atoms in adjacent unit cells. This leads to either a stabilizing overlap or destabilizing nodal planes between the orbitals, which in turn rationalizes the observed behavior of the bands along the sampled path. The mirroring of the two bands results simply from the fact that they correspond to bonding and antibonding σ crystal orbitals; say e.g. the Pb6s has a positive sign in the σ band and a negative sign in the σ* band. The figure below illustrates these linear combinations at the different points in the Brillouin zone:

What other interactions are holding the crystal together?

The σ and σ* bands discussed above are both fully populated so that their bonding and antibonding contributions cancel. However, also the Pb6p/Br4p COOP shows significant bonding characteristics in the energy range between the σ and σ* bands. Indeed, the corresponding antibonding Pb6p/Br4p bands are unpopulated as they are located directly above the Fermi level. Also in this case one observe that the three bonding Pb6p/Br4p bands are mirrored images of their antibonding counterparts, which can be understood by the same principles as discussed before. Finally, there are interactions between the Cs ions and the PbBr6 units, which can be expected to be mostly ionic and will thus not be visible in the COOP plots.